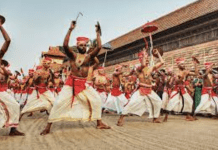

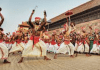

Koodiyattam, meaning “combined acting” in Malayalam, combines Sanskrit theatre performance with elements of traditional koothu. It is the only surviving art form that uses drama from ancient Sanskrit theatre. It has a documented history of a thousand years in Kerala, but its origins are not known. Koodiyattam and Chakyar koothu were among the dramatized dance worship services in the temples of ancient India, particularly Kerala. Both koodiyattam and Chakyar koothu originated from the ancient art form koothu, which is mentioned several times in Sangam literature, and the epigraphs of the subsequent Pallava, Pandiyan, Chera, and Chola periods. Inscriptions related to koothu can be seen in temples at Tanjore, Tiruvidaimaruthur, Vedaranyam, Tiruvarur, and Omampuliyur. They were treated as an integral part of worship services, alongside the singing of Tevaram and Prabandam hymns.

Ancient kings are among those listed as authors of works for these services. There is evidence of these across the ancient subcontinent during the Chola and Pallava periods. A Pallava king called Rajasimha has been credited with authoring the play Kailasodharanam in Tamil, which has the topic of Ravana becoming subject to Siva’s anger and being subdued mercilessly for this.

It is believed that Kulasekhara Varma, a medieval king of the Chera Perumal dynasty, reformed koodiyattam, introducing the local language for Vidusaka and structuring the presentation of the play into well-defined units. He himself wrote two plays, Subhadradhananjayam and Tapatisamvarana and made arrangements for their presentation on stage with the help of a Brahmin friend (Thozhan). These plays are still performed. Apart from these, the plays traditionally presented include Ascaryacudamani of Saktibhadra, Kalyanasaugandhika of Nilakantha, Bhagavadajjuka of Bodhayana, Nagananda of Harsa, and many plays ascribed to Bhasa, including Abhiseka and Pratima.

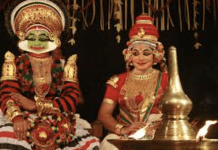

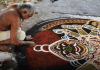

Koodiyattam represents a synthesis of Sanskrit classicism and reflects the local traditions of Kerala. In its stylized and codified theatrical language, netra abhinaya (eye expression) and hasta abhinaya (the language of gestures) are prominent. They focus on the thoughts and feelings of the main character. Actors undergo ten to fifteen years of rigorous training to become fully-fledged performers with sophisticated breathing control and subtle muscle shifts of the face and body. The actor’s art lies in elaborating a situation or episode in all its detail. Therefore, a single act may take days to perform and a complete performance may last up to 40 days.

Instruments

Traditionally, the main musical instruments used in koodiyattam are the mizhavu, kuzhitalam, edakka, kurumkuzhal, and sankhu. The mizhavu, the most prominent of these, is a percussion instrument that is played by a person of the Ambalavas Nambiar caste, accompanied by Nangyaramma playing the kuzhithalam (a type of cymbal).

Koodiyattam is traditionally performed in temple theatres known as koothambalams. Access to performances was originally restricted owing to their sacred nature, but the plays have progressively opened up to larger audiences. Yet the actor’s role retains a sacred dimension, as attested by purification rituals and the placing of an oil lamp on stage during the performance symbolizing a divine presence. The male actors hand down to their trainees detailed performance manuals, which, until recent times, remained the exclusive and secret property of selected families.

Traditionally, koodiyattam has been performed by Chakyars (a subcaste of Kerala Hindus) and by Nangyaramma (women of the Ambalavasi Nambiar caste). The name “koodiyattam”, meaning playing or performing together, is thought to refer to the presence of multiple actors on stage who act in rhythm with the beats of the mizhavu drummers. Alternatively, it may also be a reference to a common practice in Sanskrit drama where a single actor who has performed solo for several nights is joined by another.

The main actor is a Chakyar who performs the ritualistic koothu and koodiyattam inside the temple or in the koothambalam. Chakyar women, Illotammas, are not allowed to participate. Instead, the female roles are played by Nangyaramma. Koodiyattam performances are often lengthy and elaborate, ranging from 12 to 150 hours spread across several nights. A complete Koodiyattam performance consists of three parts. The first of these is the purappadu where an actor performs a verse along with the nritta aspect of dance. Following this is the nirvahanam where the actor, using abhinaya, presents the mood of the main character of the play. Then there is the nirvahanam, a retrospective, which takes the audience up to the point where the actual play begins. The final part of the performance is the koodiyattam, which is the play itself. While the first two parts are solo acts, koodiyattam can have as many characters as are required to perform on the stage.

The elders of the Chakyar community traditionally taught the artform to their youngsters. It was performed only by Chakyars until the 1950s. In 1955, Guru Mani Madhava Chakyar performed Kutiyattam outside the temple for the first time, for which he faced many problems from the hardline Chakyar community. In his own words:

“My own people condemned my action (performing Koothu and Kutiyattam outside the precincts of the temples), Once, after I had given performances at Vaikkom, they even thought about excommunicating me. I desired that this art should survive the test of time. That was precisely why I ventured outside the temple”.

In 1962, under the leadership of art and Sanskrit scholar V. Raghavan, Sanskrit Ranga of Madras invited Guru Mani Madhava Chakyar to perform koodiyattam in Chennai. Thus for the first time in history koodiyattam was performed outside Kerala. They presented over three nights koodiyattam scenes from the plays Abhiṣeka, Subhadrādhanañjaya and Nāgānda.

In early 1960s Maria Christoffer Byrski, a Polish student doing research in Indian theatres at Banaras Hindu University, studied koodiyattam with Mani Madhava Chakyar and became the first non-Chakyar/nambiar to learn the art form. He stayed in Guru’s home at Killikkurussimangalam and studied in the traditional Gurukula way.

Koodiyattam traditionally was an exclusive art form performed in special venues called koothambalams in Hindu temples and access to these performances was restricted to only caste Hindus. Also, performances can take up to forty days to complete. The collapse of the feudal order in the nineteenth century in Kerala curtailed the patronage of koodiyattam artists, and they faced serious financial difficulties. Following a revival in the early twentieth century, Koodiyattam is once again facing a lack of funding, leading to a crisis in the profession. UNESCO has called for the creation of a network of koodiyattam institutions and gurukalams to promote the transmission of the art form to future generations and for the development of new audiences besides fostering greater academic research in it. Natanakairali in Irinjalakuda is one of the most prominent institutions in the field of koodiyattam revival. The Margi Theatre Group in Thiruvananthapuram is another organisation dedicated to the revival of kathakali and koodiyattom in Kerala. Also, Nepathya is an institution promoting koodiyattam and related art forms at Moozhikkulam.The Sangeet Natak Akademi, India’s National Academy for Music, Dance and Drama, has awarded the Sangeet Natak Akademi Award, the highest award for performing artists, to kutiyattam artists like Kalamandalam Sivan Namboodiri (2007), Painkulam Raman Chakyar (2010) and Painkulam Damodara Chakyar (2012)